,

,  ,

,  ,

,

For the past two weeks, the Perseverance rover has been sending data from Mars about its geology and its potential for supporting past life.

And since its Feb. 18 landing on Mars, Luverne graduate Tony Nelson has been remotely operating “SuperCam,” sending commands to and analyzing data from the instrument.

“We’re trying to understand the geology on Mars — how those rocks formed, because they think at one time in the past our landing site had water,” said Nelson, son of Lyle and Gloria Nelson, Luverne.

“The rocks will tell the science team the history of water which will potentially tell us the history of life on Mars.”

Nelson leads project development for two of the seven rover instruments

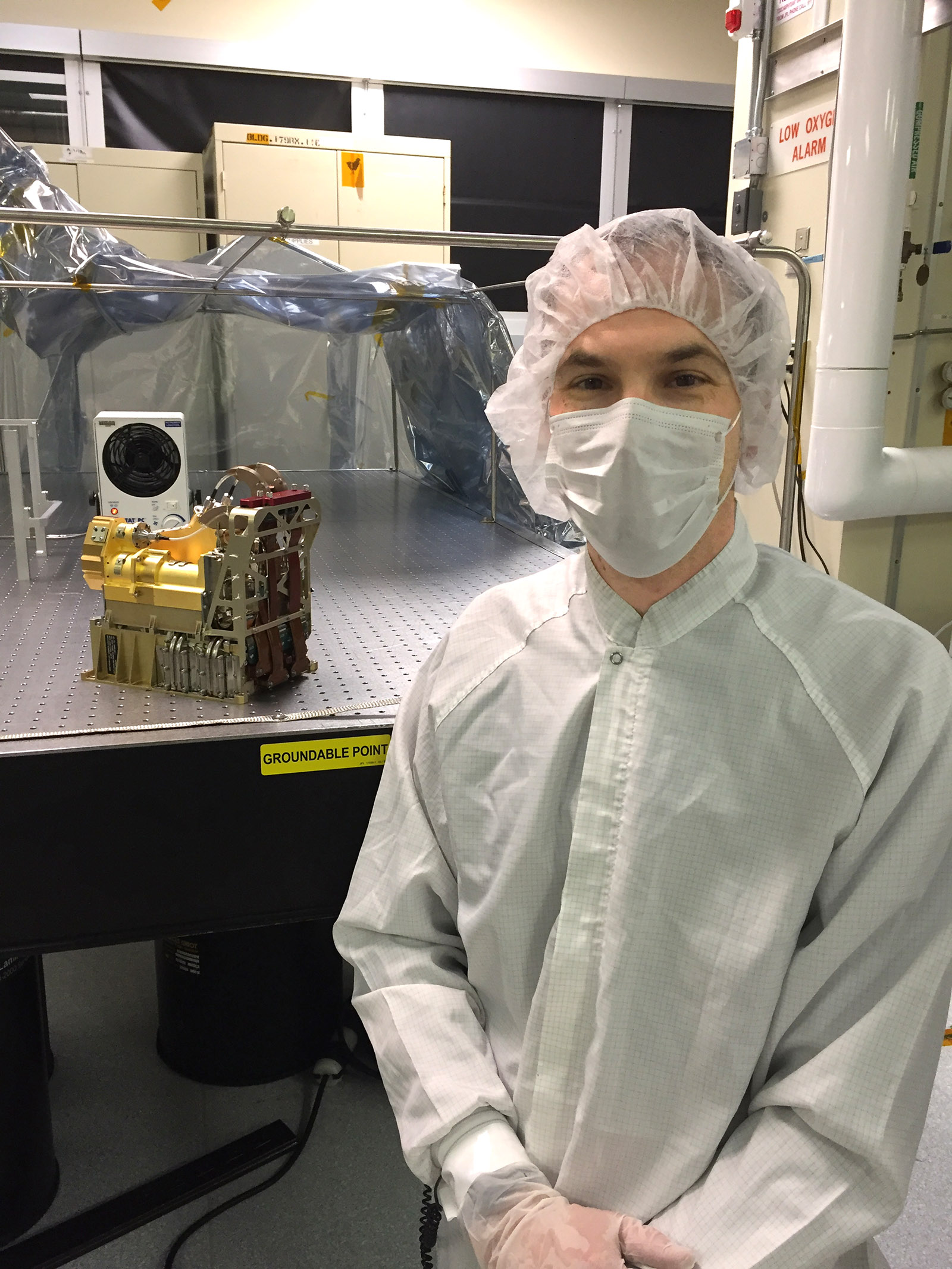

As an electrical engineer at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Nelson helped build two of the seven instruments aboard the NASA rover.

He was the project lead for the spectroscopy electronics on the “SHERLOC” instrument, which searches for organics and minerals that have been altered by water and may be signs of past microbial life.

And he was the electrical lead for the U.S. team that collaborated with France on the SuperCam instrument, which he now operates.

SuperCam examines rocks and soils with a camera, laser and spectrometers to seek organic compounds that could be related to past life on Mars.

It can identify the chemical and mineral makeup of targets as small as a pencil point from a distance of more than 20 feet.

Nelson’s team at LANL works with the French Space Agency to operate SuperCam, alternating shifts around the clock.

“At the moment we're on Mars Time,” he said, noting that it has 40 more minutes in a day than Earth Time. “We adapt our schedules to match that of the Martian day to maximize our efficiency.”

‘Seven minutes of terror’

Nelson played a lead role in developing instruments for the Mars rover “Curiosity” in 2012 when a pandemic wasn’t barring celebrations.

“When that landed, our whole team was out at NASA JPL in California,” he said. “So this has been a very different experience for us and working at home.”

Instead of watching and celebrating the Feb. 18 Perseverance landing together at the lab, team members watched from their own remote locations, somewhat joined online.

“This has been a very different experience for us,” he said. “It was just me and my wife and the cats watching the NASA channel.”

From their home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, he and Jenn anxiously watched Perseverance make its entry, descent and landing on the Red Planet.

“It was the seven minutes of terror, I guess,” he said. “It felt very real, and it was very exciting when it landed. … There have been relatively few landings on Mars; I was definitely nervous about it.”

As planned, the rover landed on a flat space in the “Jezero Crater” that scientists believe was once flooded with water and was home to an ancient river delta.

At that point, Nelson exhaled.

“It’s a one-time thing and there were a number of things that could have gone wrong,” he said.

Once it landed and data started coming in, Nelson and his team began operating the instruments that explore for signs of fossilized microbial life.

The mission can be followed on the NASA website, mars.nasa.gov.

Timeline

Nelson has been working on Perseverance since 2013 when the project sought funding — more than $2 billion.

“It takes a long time to develop these instruments for space flight,” he said. “The electronics we build aren’t like regular commercial electronics; they have to be radiation-hardened.”

He explained that Mars has no magnetic field to protect it from the sun’s radiation.

“So … we need electronics that are hardened against that,” Nelson said, “and they’re expensive and take a long time to procure and a long time to design.”

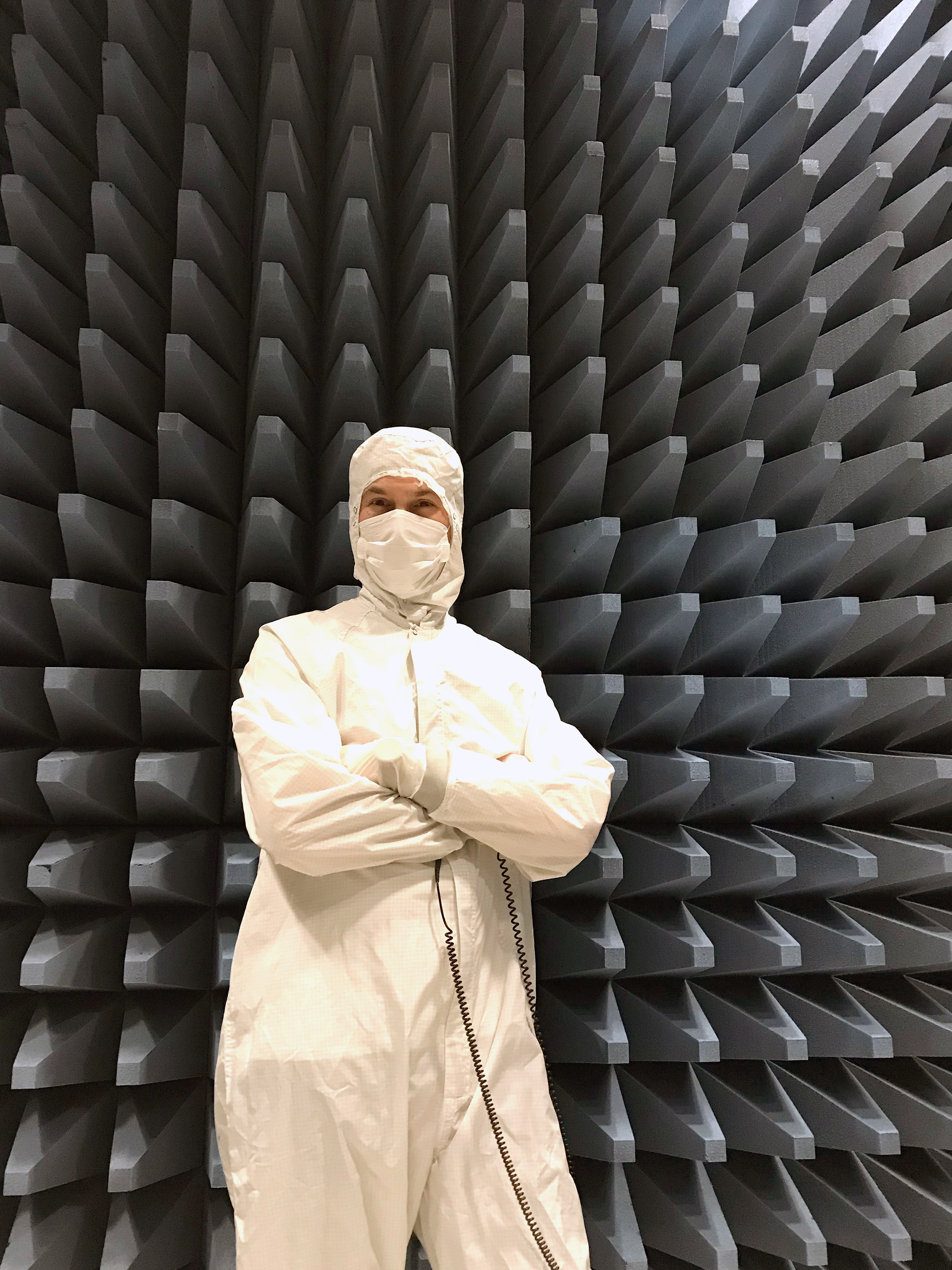

Scientists and engineers from around the world researched and developed the instruments for the rover. Its assembly was completed in mid-2019, and it was tested in the months leading to the July 30, 2020, launch.

Much of the testing happened in a metal chamber at JPL in the same simulator that’s been used since the Voyager Space Probe flights in 1977.

“The history behind it is really fun,” Nelson said. “It’s all very fun. I’m very fortunate to be able to work on this stuff.”

It took nearly seven months for Perseverance to arrive on the Mars surface after its July 30, 2020, launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

According to its mission, the rover will operate there at least one Mars year, which is about 687 Earth days.

But Nelson said it’s built to last much longer than that.

“Curiosity landed on Mars in 2012 and it’s still operating,” he said.

“It really feels gratifying to not just drop it off and hope everything works, but to be part of the team that makes sure it’s operated correctly to be used for years to come.”

After more than 20 years working as a LANL engineer, Nelson now has six instruments in space that he’s worked on.

“It takes a long time to develop these things, but at the same time it’s interesting to be able to be so involved from the design to be actually using our instruments,” he said.

“I have to say working on the rover is most gratifying because it’s something that public is interested in and we can communicate about it.”

Nelson graduated from Luverne High School in 1993 and got his electrical engineering degree from the South Dakota School of Mines in Rapid City in 1997.

He completed a master’s degree at Vanderbilt University in 2000 and has been working for LANL in Los Alamos, New Mexico, since then.